Decriminalising Ornament: The Pleasures of Pattern: The Sympathy of Illustration

Published in the Journal of Illustration 6-1,2019

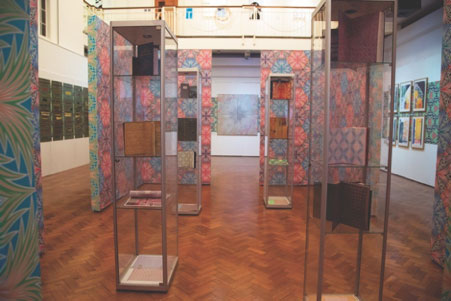

This article reflects on the research exhibition Decriminalising Ornament: The Pleasures of Pattern held in the Ruskin Gallery in Cambridge in November 2018 in conjunction with the International Illustration Research Conference of the same name. The exhibition focused on the practice, tradition and art forms that emphasize ornamentation and printed pattern as a meaningful part of the illustration and design experience. These ideas were not just embodied in the individual works but through an exhibition design in which visitors were enticed into a carefully calibrated sequence of decorated enclosures in which the works were displayed.

The exhibition sought to foreground its guiding principle that the decorative is no mere trivial adornment but a profound dimension of aesthetic engagement that reveals a material–human relationship, a relationship based on a dialogical interaction between human action and material forces and properties, something the artist, architect and theorist Lars Spuybroek calls sympathy. Spuybroek presents his concept of sympathy as ‘the deep-rooted engagement between us and things, deeper than any aesthetic judgement would allow’ (2016: 107). Through the consideration of the role of the decorative in the exhibited works, this article explores Spuybroek’s concept and makes a case for sympathy not only as a useful term to describe the decorative, but as an inherent, engaging and essential part of illustration.

Figure 1: Exhibition overview, Decriminalising Ornament: The Pleasures of Pattern,. Ruskin Gallery, 2018, Cambridge.

In his book The Sympathy of Things, Spuybroek (2016) presents sympathy as an essential humanizing quality which can be found in the appreciation of patterns, textures and decoration found on the surface of things. This is something that has been lost over the Modernist decades, but which, he argues, needs to be reconsidered as essential in the appreciation of objects and artefacts.

Although Spuybroek excludes mediated images from the ability to harbour sympathy, as he sees them as disconnected references, he does not specifically direct himself towards illustration. As illustration is often overlooked for its specific expressive qualities, which sets it apart from other image forms, it is therefore important that special attention is paid to the nature of illustration, which I would argue would not only allow illustration to be exempt from Spuybroeks exclusion, but makes the concept of sympathy actually central to illustration. Sympathy describes the fundamental resonance not only through illustration as an artefact but also in the role of the illustration itself within its published context. Through the consideration of the role of the decorative in the works included in the exhibition, this article makes a case for sympathy as an intrinsic, engaging and essential part of illustration.

This exploration first requires a more extensive consideration of the significant presence of texture and pattern within illustration, and how this plays out in the works exhibited in the exhibition. This is followed by an examination of Spuybroek’s idea of sympathy, using his conceptual framework based on ideas shaped by amongst others the pre-modern art critic and naturalist John Ruskin, and the philosophers Theodor Lipp and Henri Bergson. I contextualize this examination through the individual contributions to the show and the artists’ personal descriptions of their work in the exhibition catalogue (Anglia Ruskin University 2018). This leads to a proposition that sympathy could be understood as a fundamental property of illustration and will shine a light on the appreciation of the decorative as part of the role of illustration.

‘[Pattern and ornament] are strategies for thinking and making that have rich histories that can and must be continually re-imagined. They can be used as framing devices or carriers for critical or narrative commentary’ As (the designer and theorist) Daniël van der Velden says, “Playfulness and layers, multiple narratives, embedding history, seeking relations, and also political implications are better expressed in a visual vocabulary less dogmatic and more rich than Modernism” ’. (Twemlow 2005: n.pag.)

The above is the final paragraph of the article The Decriminalisation of Ornament (Twemlow 2005) whose title inspired the name of the conference and exhibition. In the initial article Twemlow points to the slow but steady re-engagement that our culture has with decoration and ornamentation. We could take these words as praise for pattern and ornament, part of a general renewal of interest in current visual culture. But interpreting these words in relation to illustration, highlights the role of pattern and ornament as an essential part of the illustration, as well as pointing to how illustration itself could also be seen as having a decorative function within its published and reproduced context.